Weekly News Review Feb 26 – Mar 3 2024

March 4, 2024

Weekly News Review Mar 4 – Mar 10 2024

March 10, 2024Today, we will take a look at exactly how China became the rare earth superpower it is today, but first, let’s take a trip back to 1987 when the seed was planted.

In the 1980s, the USA was the dominant market leader in the global production of rare earths. Then, in 1987, the premier leader of China, Deng Xiaoping, AKA the architect of modern China, made a shrewd prediction; he said: “The Middle East has oil, China has Rare Earths”.

Almost exactly to the day, 35 years later, the president of the European Union, Ursula van der Leyen, stated that “rare earths” are fast becoming and will become more important than oil and gas. Watch speech extract here: https://vimeo.com/910834132

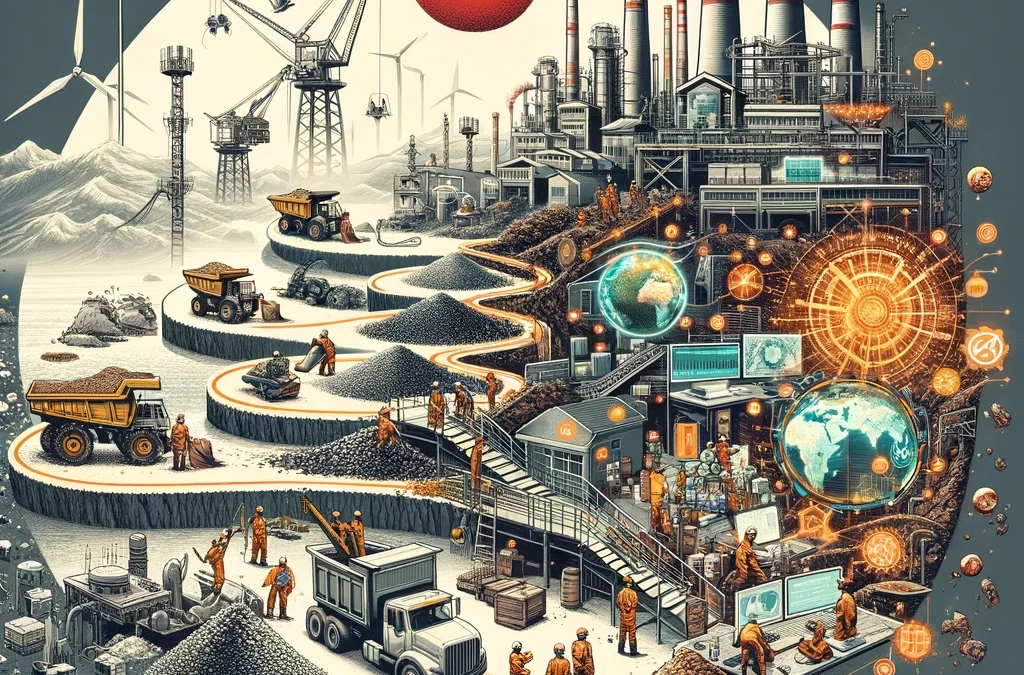

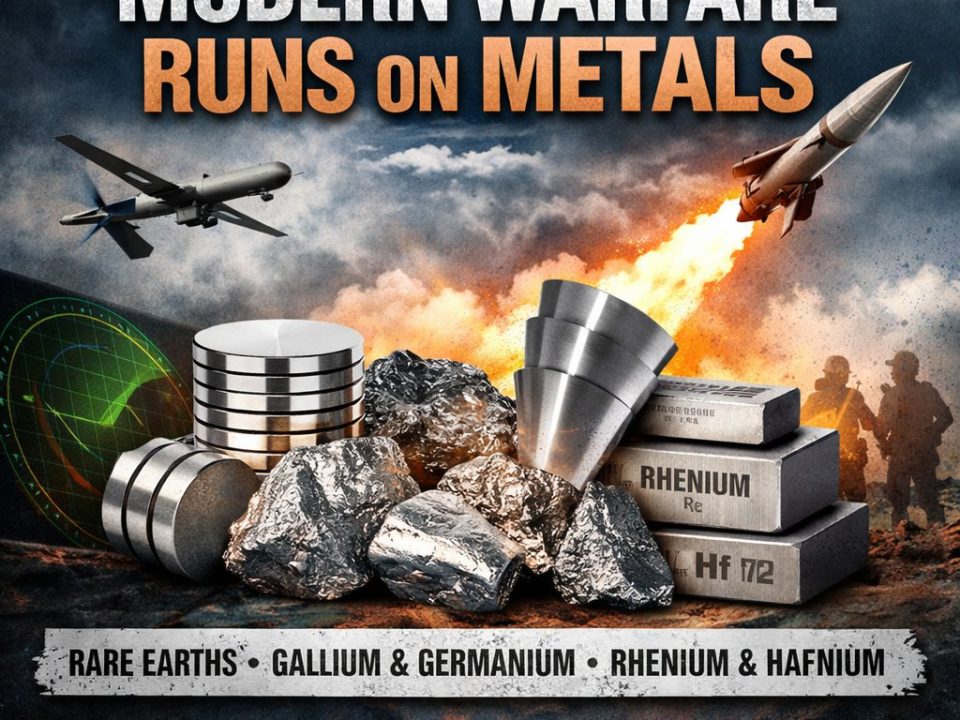

We now know that China understood long before the EU that rare earths would become the backbone of manufacturing in the 21st century. China understood that rare earths like Neodymium and Terbium and Technology metals like Gallium and Germanium would be the downstream raw materials that ultimately become trillions of dollars in upstream GDP. Today, technology, metals, and rare earths are critical to all nations’ economic prosperity and, increasingly, military capabilities.

2 GIANTS, 20 YEARS, THE GREAT CONSOLIDATION:

It is almost impossible to mention rare earths in a sentence and not mention China as well. The Middle Kingdom possesses the world’s largest known deposits of these critical minerals and has a virtual monopoly on their mining and processing. The Bayan Obo mine in Baotou, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is known as the “world capital of rare earths” — a status resulting from decades of planning and targeted political decisions.

The country’s nuclear program is the key to China’s current dominance in rare earths. In the 1950s, critical technological foundations were laid for the process, which developed around 20 years later to separate raw rare earth materials. The new method marked a change in the global division of labor.

Until then, China had exported its raw materials to other countries for further processing. After introducing the new methods, the old relationship gradually began to reverse. In the mid-1980s, China replaced the U.S. as the world’s largest producer of rare earths. Exports increased, while prices for rare earths dropped due to overcapacity.

Between 2002 and 2005, many other suppliers found themselves unable to compete with China’s rare earth supply and pricing, which led to the closure of several mines, including the formerly important Mountain Pass mine in the U.S.

However, this increasingly dynamic production growth created a fragmented industry in China with thousands of mines, some of which were illegal, competing fiercely with each other and often circumventing environmental and safety regulations. This situation depressed prices, so the government decided on a far-reaching plan to clean up the market and give it more clout.

REORGANISATION AND A LONG BREATH:

The State Council of the People’s Republic considered consolidating the solution and approved the corresponding plans in 2002. At the same time, it initiated a reduction in the number of market participants for 14 other resources — antimony, bauxite, lead, iron ore, gold, potassium, coal, copper, manganese, molybdenum, phosphorus, tungsten, zinc, and tin — in addition to the rare earth group.

In the rare earth sector, the reasons for the project were complex. Above all, the Chinese government wanted more control over pricing. Due to the fragmented market, Beijing’s influence in this area was limited despite the country’s international quasi-monopoly of the extraction and processing of critical raw materials. Individual companies sometimes undercut each other. The Chinese Minister of Industry and Information Technology, Xiao Yaqing, was still complaining in 2021 that China was selling rare earths at the price of earths rather than the price of something scarce.

Beijing also hoped consolidation would simplify decision-making and enforcement processes in the sector. Growing environmental concerns and a plethora of illegally operating mining companies connected to smuggling activities were cited as additional concerns that consolidation would address. Another factor supporting market concentration was the goal of upgrading quality in the industry. Consolidation would give the government more influence over the industry’s ongoing development and modernization.

A FRAGMENTED MARKET AND LOCAL RESISTANCE: THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE.

The project, which has been running since 2002, envisaged only two large companies for rare earths in the long term: one in the north and one in the south. This choice was due to natural geographical conditions and the different mining histories in the individual regions.

In the north, ores are extracted from open-pit mines that predominantly contain light rare earths. In the south, heavy rare earths are extracted from ion adsorption clays. These clays are formed wherever strong weather conditions prevail. They are currently economically significant only in southern China and neighbouring Myanmar.

The plan also envisioned a consolidation of the downstream processing industry. In the north, processing companies have settled in Baotou, approximately 150 kilometres from the world’s most significant rare earth deposit, Bayan Obo.

The South was also characterized by a large number of players fighting for market dominance. Due to the large number of companies, the consolidation plans were (unsurprisingly) met with resistance. Pushback also came from provincial governments. They received taxes from locally operating companies, whereas those from centrally managed companies would flow to Beijing. Consolidation progressed far more smoothly in the north, mainly because its mining industry had been far more homogeneous for decades and in the hands of individual large companies.

SLOW BUT STEADY: CONSOLIDATION IS MAKING PROGRESS:

On the surface, consolidation progressed slowly as the government gradually granted fewer mining rights. By 2012, the number of licenses issued had fallen from 113 to 67, with 90% of these rights ending up with companies that later became part of China’s six largest rare earth companies, the so-called Big Six. Exports were also concentrated during this time, with the government authorizing only 22 companies to export rare earths in 2011. In 2006, there were 47.

In parallel to the measures in the domestic market, China also sought more control over exports. In 2006, the People’s Republic successfully introduced quotas limiting rare earth export quantities. China gradually tightened these quotas.

In 2010, the Chinese customs authority even temporarily halted the export of rare earths to Japan due to a simmering trade dispute, even though this was never officially confirmed. Fears of a nationwide supply freeze caused rare earth prices on the international market to rise to a level that has yet to be exceeded.

In 2012, the USA, the European Union and Japan filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO) against further tightening export quotas.

The reason was that China violated applicable law by denying access to critical raw materials. In 2014, the WTO ruled against the People’s Republic, which was forced to drop the export quotas.

THE FIRST MILESTONE, THE BIG SIX, EMERGED.

In 2012, the rare earth industry in the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia came under the complete control of a subsidiary of the iron and steel group Baotou Iron and Steel, which has been operating under the name China Northern Rare Earth Group since 2014. After the consolidation of 35 producers, the rare earth industry in China’s north was controlled by one company.

Consolidation also made gradual progress in the south, but it wasn’t until 2016 that the first sustainable centralization was completed. By consolidating hundreds of companies into five — Xiamen Tungsten, Minmetals Rare Earth, Guangdong Rare Earth, the rare earth division of Chinalco (Aluminium Corporation of China), and China Southern Rare Earth — the industry in the south was now also streamlined in organizational terms. By 2016, together with the China Northern Rare Earth Group in the north, China’s entire rare earth sector was in the hands of six large companies, the so-called Big Six.

THE 2 GIANTS EMERGE:

The next step on the way to creating two market-dominating groups took place in 2021. Three of the Big Six — the rare earth division Chinalcos, Minmetals Rare Earth, and China Southern Rare Earth — merged under the name China Rare Earth Group (CREG). The three companies each held a 20 per cent stake in CREG. In addition, the Chinese government held a direct 30% stake in CREG in the form of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. The remaining ten per cent was distributed among smaller research companies.

The takeover of Guangdong Rare Earth in 2024 was the last official step for the time being in the streamlining of China’s rare earth industry. This left Xiamen Tungsten as the only independent company. However, Xiamen Tungsten and CREG had been cooperating since 2023 in a joint venture in which CREG held more than 50 per cent—the scheme aimed to pool production quotas. The days of Xiamen Tungsten’s independence were, therefore, already numbered.

Beijing published new production quotas in February 2024. Only two companies are listed: the China Northern Rare Earth Group in the north, which is solely responsible for light rare earths, and the China Rare Earth Group in the south, which is also permitted to mine heavy rare earths.

Since Xiamen Tungsten is no longer listed, but since its quotas are combined with CREG, it can be deduced that the consolidation plans have now been implemented.

This marks the end of a project that began over two decades ago.